Japanese Layered Steel: San-Mai, Warikomi, Mono-steel, and Other Knife-Making Techniques

We love Japanese knives. They’re beautiful, many of them are handmade, and they tend to get sharper and hold their edge for longer than conventional kitchen knives.

You may ask, “But why do they stay sharp longer?”

Because they’re made out of harder steel, of course! The steel your knife is made of is one of the most important factor to consider when buying a knife. Soft steel, like what you’ll find in Arcos Products and many widely available brands of kitchen knives, is very durable but doesn't hold a razor sharp edge for long, or maintain it like a Japanese blade can. This means they also tend to be much thicker in order to help them hold an edge. Imagine trying to thinly slice a tomato with an axe. No fun.

While Japanese knives are generally thinner and sharper, not all blades are created the same; there are many techniques blacksmiths and manufacturers use to achieve different results. Lets go over some of the different methods these guys use to achieve true slicing nirvana!

San-mai or three-layer Knives

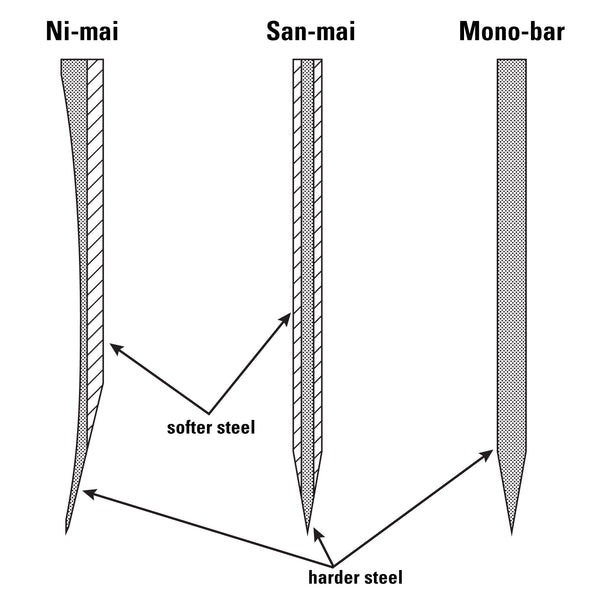

By far, the most common type of knives you’ll see in our shops are san-mai. San-mai simply translates to “three layer”, referring to three layers of steel used to make the knife. It all stems from a pretty simple idea—the harder your steel is, the better your knife will hold its edge. As steel becomes harder—either through adding elements such as carbon, or by heat treating—the more fragile and brittle it can become. Hardness is desired for extreme edge retention and sharpness, but hardening your steel can create a pretty serious problem: your knife can chip easily or even snap right in half if you drop it. San-mai construction solves this problem elegantly. By forge-welding softer steel onto either side of the hard steel, you give the blade a great deal more structural integrity without sacrificing its ability to hold an edge. It's like a security blanket for your knives! If you look closely at the edge of your fancy Japanese knife, you might see a squiggly line. This is where the hard core-steel pokes out from in between two layers of soft cladding steel - like a slice of ham hanging over the edge of your sandwich.

Not all blacksmiths produce san-mai knives using the same methodology, however. The Haruyuki Kokuto series, one of our favourite factory forged lines, takes advantage of some pretty sophisticated technology. They work with “pre-laminated” steel, which has been perfectly forge welded together in a steel factory for extreme quality and consistency. They then cut their knife shapes out of a large sheet of san-mai steel with a cookie cutter-like punch. Meanwhile, our pals like Fujiwara-san forge weld the steel themselves by stacking three layers together and forging it under their springhammer. While this takes a lot more time (and money), the forging has beneficial effects on the steel and the end result is a phenomenal knife.

At Moritaka Hamono, a family of blacksmiths who have been forging swords and knives for over 700 years, they employ an older technique called Warikomi which is a bit different, but achieves very similar results. A soft metal is heated and split like a hot dog bun. Then, a bar of hard steel is inserted into the split (pictured above) and forge welded to the softer material. The result works just like san-mai while honouring the traditions of the Moritaka family. Instead of steel cladding, the Moritakas actually clad their hard core steel in iron!

There is no shortage of variety in san-mai knives. Some are made with two different stainless steels in both cladding and core, two types of carbon steel, or a combination of both. Some of my favourite knives are made with a super hard carbon steel core and have stainless steel laminated on the outside to make maintenance easier, as carbon steel can rust if not properly cared for. Unlike full carbon steel knives, these 'stainless-clad carbon' blades only rust at the edge and are much easier to keep free of oxidization. Check out this stainless-clad carbon blade from Fujiwara-san:

Ni-mai or two layer Knives

Most single bevel knives use a similar concept as the san-mai for protecting harder steel, but they’re typically made using a technique called ni-mai, which translates into “two layer”. The hard, brittle steel does the cutting while a single layer of softer steel is forge-welded onto the face of the knife to keep it from being too fragile. Single bevel ni-mai knives are also sharpened and ground quite differently. The face of the knife with the softer steel features a steep bevel, while the hard steel on the back of the blade is slightly concave, creating an air pocket against food that helps it release from the blade. See below:

Mono-bar/ Honyaki Knives

The honyaki method, the oldest of the old school, is a mono-bar technique that has been used to make swords for hundreds of years. If you’ve been paying attention, I bet you can guess what “mono-bar” means (hint: one layer). Less than 1% of knives produced in Japan still use this time-honored technique, but the resulting blades are considered by many knife nerds to be the finest on the planet. Put simply, a single piece of steel is differentiall-hardened, meaning the edge is super hard, while the spine is soft and shock-absorbant. There is too much to learn about this very difficult technique to cover here, but Chris wrote them their own blog post to pay respect to these beauties.

All this said, not all mono-bar steel knives are that fancy The most basic method of mono-bar construction tends to create knives that are okay at holding an edge, but make up for their lesser edge-holding ability by being, by-far, the most durable Japanese knives available. The Sakai Takayuki SK4 blades can take a bit of a beating, are easy to hone and sharpen, but aren’t able to hold an edge quite like most of our harder blades. Make no mistake—they’ll still hold a much keener edge than that set of nine that Canadian Tire sells for $23, and they won't break the bank either. If you’re worried about your knife roll getting jacked because you’re working somewhere sketchy, these are absolutely the right knives for you!

Notice the lack of a cladding line on the SK4 series?

Notice the lack of a cladding line on the SK4 series?

So what’s the right choice? Which knife is the best? Well, it all depends on what you want it to do. At the end of the day, knives that are made out of the hardest steel hold a sharp edge the longest. San-mai, ni-mai, and honyaki knives are truly the most capable in this regard, but every knife has its strengths and weakness. Many of my favourite knives are san-mai, I use them every day for meat and veggies, but keep them away from bones and frozen food. Mono-bar blades need to be sharpened more often but are excellent for tougher jobs or lending out to a coworker. Honyaki knives are gorgeous collectors items worth having in your kit, and certainly not the knife to leave at work unsupervised.

I recommend having a good variety of tools in your arsenal that specialize at different jobs. You know what they say - If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. I use san-mai knives for everyday work, a single bevel ni-mai for fish, and my mono-bar Sakai Takayuki SK4 Honesuki when I’m butchering chicken.